National Photography Symposium London 2012 from Barbara Nickl on Vimeo.

Monthly Archives: May 2012

Keynote: Peter Kennard

Written by Sian Gouldstone, http://mythoughtsarecurly.wordpress.com/

I had expectations of the National Photography Symposium before I sat down to listen to Peter Kennard, clearly. They were mainly centered around the asking of original questions in photography. I was interested whether we would ask questions that haven’t been asked before, repeat or re-analyse those that have; answer questions for the first or last time; or whether we would not be able to answer questions at all. The more I learn and think about photography, the more of an enigma it becomes and this is what drives me… to teach, to learn, to discuss, and to ask and to try to find answers to the questions posed in relation to photography practices today.

Peter Kennard was interesting and driven, he offers and he asks questions of photography himself. It’s role and its procedures are scrutinized. Before all else though, I must point out that Peter Kennard is alive, still. He declared this to us himself, in person, in response to all the doubters… Ladies and Gentlemen; Mr Peter Kennard…

Kennard cites Heartfield, Rodchenko and Brecht as influencing and inspiring. I don’t know a thing about Brecht, I’ll admit; but I do know a thing or two about Heartfield and Rodchenko. Here we are, straight into montage and straight into politics with no introductions. Heartfield and Rodchenko made work that communicates and questions, it is of its time and more. It has a voice, one that speaks and asks, about the past, the present and the future. It is propaganda; it is inspiring. Peter Kennard, quite copiously, also makes work that communicates and asks questions. His work is propaganda, I guess, and it is inspirational.

Through this first session at the NPS, we were given information, factual and fictional, and asked to consider a range of issues through our relations with politics, plagiarism, Palestine, posters, poverty, printing & the photo-montage of Peter Kennard! The power of montage brings up all manner of issues, and despite the years that Kennard has been working, the issues raised by his work are still current – like Heartfield and Rodchenko, his work speaks and asks about the past, the present and the future. So far as I can see, it has always had a place, quite central, in a discussion around power and seeing in visual cultures.

Peter Kennard is of the old school of montage; paper, scissors, knives and glue. He himself explains that his work needs to be seen, and to be understood, quickly. So it is simple.

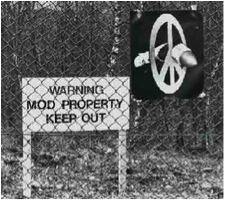

Peter Kennard, Broken Missile, 1980, photomontage

The work Broken Missile is a photograph that Kennard took, of a child’s toy and a spray-painted piece of cardboard. It is unfussy and is subject to interpretation, quickly.

Kennard refers to this work on his website:

‘The point of my work is to use easily recognisable iconic images, but to render them unacceptable. To break down the image of the all-powerful missile, in order to represent the power of the millions of people who are actually trying to break them. After breaking them, to show new possibilities emerging in the cracks and splintered fragments of the old reality.’

It is the simplicity of Broken Missile and its subsequent re-presentations that makes it a fascinating piece. It provokes an interesting discussion and asks obvious questions about political issues. It was the questions related to plagiarism in photography that I was more interested in though – we have seen this image plastered across t-shirts and placards; used, used and re-used. At this current time, 30 years after Kennard made Broken Missile, we are within the motions of a great change in the way in which we view, make and use images. Plagiarism and pastiche are key ways in which we are changing our understanding of the past, present and future of photography. Where do we stand?

A poster of Broken Missile taped to the fence of Greenham Common by a protester, 1982

Don’t think for a moment though that plagiarism offends Peter Kennard. His use of iconic symbols extends to incorporate iconic paintings. Haywain with Cruise Missiles was a response to the siting of US missiles in Britain. In this, Kennard uses Constable’s Haywain to reinvigorate discussion on political issues, to symbolise the much-loved British landscape and possibly to metaphorically refer to the invasion of something that doesn’t necessarily belong to you.

Peter Kennard, Haywain with Cruise Missiles, 1980, photomontage

Right now, I am introducing ideas from Kennard’s talk, but large debate on plagiarism, pastiche, mimic and copyright can ensue… and it would be right up my street! It raises the very contemporary discussion around authorship and ownership, audience and meaning. How are they changing in a very digital and accessibility savvy period? Kennard himself was quite clear that he doesn’t have the legal team to govern the dissemination of his images beyond the uses that he creates them for. He goes on to say, however, that people will make money from his work, but if in the process of this happening, the money goes to the correct cause intended by his work, then he has no problem.

The rights to use images, who can see and use images, and how images are shown are all relative to Kennard’s approach in one way or another. He tells us that his shows, and other work, can be censored and filtered politically. Restrictions are literally, or metaphorically placed around work shown in public. This leads to one of the aspects of Kennard’s approach to his work that speaks to me of questioning. He refuses to be bound by the exhibitory nature of his work. Kennard shows in as many different and engaging ways as possible. On every seat in the auditorium was a newspaper page, and advert for his new show. Kennard showed manual work, darkroom work, gallery work, public intervention, digital work & interactive work.

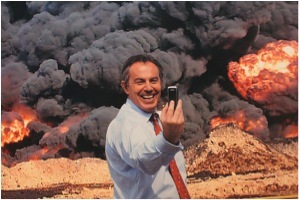

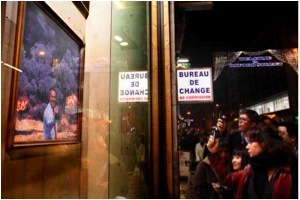

The Self Portrait of Tony Blair was shown in a shop window, ‘Santa’s Ghetto’, on Oxford St; a piece that allowed interaction from the public, that touched on a contemporary zeitgeist related to self-imagining and identity.

Peter Kennard, from Santa’s Ghetto, 2006

…in the ghetto’s window on oxford street, London (http://www.kennardphillipps.com/)

Kennard also spoke of the café that he helped create in the City of London in Leadenhall market. The café offered soup for bankers, calculated at the same proportion of their average salary as an average African worker would pay – soup was charged at £111 per cup.

The issue of subversive work in public spaces raised questions about the traditional values of the art world. How accessible is art everyday? Do traditional artistic values and accessibility to controversial imagery limit photography as a genre? Kennard used an example where Orange censored a Christmas message that he’d made. Orange subsequently withdrew the work, as they needed to bear in mind their corporate identity. The irony of this is that Orange lecture on censorship, and yet appear to censor work themselves.

The last thing that Kennard talked about was his book @Earth. @Earth is a sequence of pictures, which is intended to be read as a whole sequence. It is presented as a series of folders – each opening to reveal its series of images. Kennard says that a montage is a sentence. With this in mind, @Earth and can be read with a strong, intentional narrative. In some sense it is a retrospective thus far of Kennard’s career.

Kennard is keen to stress that the work he produces is primarily in montage. Where collage stresses no similarity or reference between the images it uses, a montage does. The montage recognises skill on a surface, its images work together to communicate, to relate issues and to ask questions about the nature of what it presents. This is a metaphor it seems, for the careers work so far of Peter Kennard.

Peter Kennard can be found at http://www.peterkennard.com/ and at http://www.kennardphillipps.com/.