[You can find links to reports on Day 1 and Day 2 of the NPS2018 here.]

The final blog post on the National Photography Symposium 2018 comes in the new year of 2019. Timely, as there have been many developments with those who contributed (as you are soon to discover). Also further relevance, as this blog post concludes with what can be framed as a set of new year’s resolutions – “campaigns for the future” – for Redeye Network moving forward, where we’d welcome you all getting involved.

Day 3 of NPS2018 opened with Lewis Bush presenting on ‘The Algorithmic Photojournalist’ – the algorithmic automation of photography through photojournalism and “intelligence gathering”, and technologies and the politics that underlie these technologies. For example, AI and its application to other areas of practice including international development, medicine, war and conflict, and the space race. He stated: automation is not how we take photographs, but how they are made and circulated, also how we use the way images are circulated to trace things that are hard to photograph directly. The automated analysis of images appeared in the 1950s (including in science fiction), while today, we are totally reliant on algorithms due to, and as a, technology. Lewis sees these algorithms as a form of knowledge in themselves, and references back to Kai Bastard’s presentation on the previous day as a good example of how AI can hide (racial) bias within an algorithm – where bias and politics are often unintentionally written within.

Lewis coined this as “other ways of looking” (which to me, was a contemporary revisioning of John Berger’s “Ways of seeing”) and questioned ‘why does AI matter?’ acknowledging it has become a “buzzword” and will either ‘be the end of us all, or it will do amazing things […] truth is it will be a mixture of the two […] positive and negative.’ Also, the historical understanding of photography as a democratic medium (e.g. of truths) yet used for tyrannous purposes (e.g. fake images) however, we don’t talk enough about what we mean by democratic photography or the democracy of the technology.

“Photography’s strength is also its undoing […] before, the problem was the limits of the human eye, now we are facing this problem we have always had […] a monopoly on the interpretation of images […] ‘there are too many images in the world’ isn’t a valid comment to make anymore.”

Lewis Bush. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Lewis stated the proliferation of cameras and the way images are taken and used have changed; as such, the photograph has changed to no longer be a material thing:

“Photography is completely immaterial […] we are looking at something that has been mediated through multiple algorithms and computer codes […] mediated slices of reality.”

Throughout his presentation, he reiterated it is important for photographers to address these issues whilst the technologies are in development, where we are in the lucky position to shape how they get used/terms of use. It is not just about surviving the impending revolution of automation, it’s becoming part of it. He concluded by asking two key questions: What is the impact of automation and Artificial Intelligence going to be on journalism? What potential uses (good and bad) and how can we adjust for that? Discussing “citizen journalism”; automation technology for facial recognition/verification; technologies’ struggle with the nuance of context, and the judgement and memorability of the image – how do we pull these things together for use in the newsroom? He cited the visual media reasoning (VMR) package DARPA as the next step, which long-term will end up filtering down to us.

“If you don’t want to be automated out of a job – do something creative.”

The Use & Abuse of Photographs: Panel. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

The first panel of the final day of NPS2018 was on ‘The use and abuse of photographs’ opening with John Walmsley (who’d also presented on the day prior) discussion on fair pay, intellectual property, copyright and the copyright act 1988 – what do you do if people take, steal and use your work? He set a tone of responsibility for this panel, emphasising there is nothing wrong with making a living from being a photographer, where photographers must get paid for what they do. As raised throughout Day 1 of NPS2018, he reiterated the key role schools and colleges have to play in the education, infrastructure and change on these issues.

John Walmsley. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Next, Jennifer Doohan presented the paradox of “imitation versus inspiration” – stolen moments and scenes recreated, questioning, what can photographers do in this situation? Can such imitation be turned into a benefit? Legally, these photographs are seen as an imitation, not a copy, however if it was a drawing or painting there could be an infringement. She described her photography process as ‘creating in the moment and reacting to things, where there is no plan […] there may be a route to follow or a rough guide […] there is a magic to it, but it can be stressful.’

“If you want to be original, be ready to be copied.” – Coco Chanel

Jennifer questioned, was my idea copied? Is it a derivative work? Is imitation a new norm to be accepted? Is this the world we are living in? Again, much like the other speakers of the day, she emphasised the importance of taking responsibility for your role and work – ‘to look after your work is not a bad thing, take yourself seriously.’

Jennifer Doohan. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Following lunch, Philip Walker presented ‘The Blockchain Potential’ – a way to tokenise photography to sell, using the example of the ‘Forever Rose’ to visualise the process. Sold for $100,000 in the form of a share (x 10) – buyers never received a photo, or a portion of the photo, they received a bit of code – is this “the emperor’s new rose”? Often understood as an abstract concept, the work becomes a digital asset, therefore, how can we give it ownership and value? Blockchain exists to record and track anything of value based on the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Here, Blockchain is used as a time-dating digital transaction – a distributive legislative technology, creating provenance by checking the origin of where somethings come from. It is a public and transparent presentation of data. An image is timestamped with a hash, also an encrypted representation of the image. However, Blockchain doesn’t store the image. It becomes an open and accessible ledger; part of a decentralised peer-to-peer system – there’s no middle man involved, no longer reliant on people – this is known as the “trust protocol”. The benefits are there is no single point of failure, autonomy, copyright standardisation, speed or scarcity. However, there still needs to be a regulation standard put in, in terms of centralising the checking of copyright. Referencing back to Lewis’s presentation earlier in the day, how can we trust this type of algorithm? Does it have scalability (computing power)? Who has ownership and value (of your image)?

Philip Walker. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Another consideration is the social acceptability of a digital asset, as much as a physical asset, therefore, trying to create an environment where it is not socially acceptable to steal in the digital realm. Paul Herrmann concluded by emphasising the need for protecting digital content in the long-term, including copyright, derivate works and the distribution of works, and whether or not blockchain is part of this process.

The Use & Abuse of Photographs: Panel. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

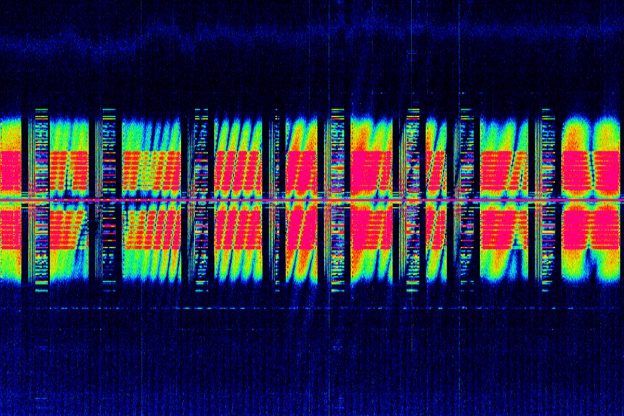

After lunch, continuing the theme and narrative of the day, was Thierry Secretan’s discussion on ‘Who kills our metadata?’. He opened by stating we are in a society that is turning website visitors into customers, where the internet is driven by keywords and data, specifically known as “metadata”, yet many don’t understand its potential or importance. Also, many photographers do not acknowledge the seriousness of protecting creative work through these digital processes. As such, how can technologies be developed to retrospectively tag metadata? He asked how we might identify the 97% of images on the web that have no metadata (and so are seen as orphan works), and can this be monetised? He cited the development of IMATAG – intelligent image tracking technology for photographers – as an alternative to give “the right images, with their image rights”. Acting as a watermark that is algorithmically embedded in an image so metadata cannot be stripped to enable you to look – look, download – look, download and share – professionally and appropriately. After Thierry’s presentation, Paul Herrmann stated that the general adoption of metadata is more important that getting it right in every case; it is in everybody’s interest to use metadata – how do we encourage this as best practice?

Thierry Secretan. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Following a short afternoon break, came a panel discussion many of the delegates had been waiting for throughout NPS2018’s three-day event – ‘Rebalancing the bias – is the future female’ with Tracy Marshall, Hilary Wood, Maryam Wahid and Mandy Barker. Tracy Marshall chaired the panel, opening with the provocation, are we moving forward from the #metoo movement with female photographers?

Rebalancing the Bias – Is the Future Female? Panel. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Hilary Wood cited the artist-led project she recently curated entitled ‘209 Women’ – 209 portraits of women members of parliament by women photographers – marking one hundred years after women first gained the right to sit in Parliament as MPs and vote, also the value and potential of what these 209 women can do for the future. The project was to gain visibility for women across photography, confidence for those involved, create peer support networks, and to encourage discussion of things that we can do towards practical change in the industry, whilst highlighting continued gender imbalance across parliament and the arts and cultural sector. [‘209 Women’ launched before Christmas and is currently show at Portcullis House, London, until 14 February 2019, where only a few free tickets are available (only dates for 1 February left!), then touring to Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool.]

Rebalancing the Bias – Is the Future Female? Panel. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

Maryam Wahid discussed her practice as a representation of herself as a British Pakistani person and Muslim women – a controversial and debatable topic in Britain, something she was clearly passionate about including the notion of home. When she visited art galleries here, she stated it was important to understand why there was little representation of herself “as a Muslim girl or Asian in Britain”, as it certainly didn’t reflect her community in Britain. Returning to Professor Elizabeth Edwards’s quote on Day 1 of NPS2018 – photography as a hopeful medium – Maryam’s work tells her story as a second generation Muslim woman, with a focus on the hijab whilst referencing religion and culture. Also, the differences in generations including social structures and gender roles used to represent their identity, which is changing in young British Asian women. She wants her work to be seen to celebrate community in Britain, of which she is proud – women as essence of the community, often underappreciated when there is a lot of hard work there to continue cultures and their histories. [Maryam’s work has recently been profiled through the BBC Asian Network.]

Mandy Barker presented on design and branding for positive social impact with firms taking ownership of arts and cultural projects through a collective way of working to tackle topical issues – it lets them, as a company, be heard towards meaningful results – “we rise by lifting others”. Also, highlighting that women have not had the same space that men have; it is often the case that the higher you go, the fewer women there are. It is about work AND outside of work, where challenging conformity can be uncomfortable – we must send tiny ripples of hope (back to the hopefulness as outlaid at the start of Day 1 of NPS2018). It is about unlearning society, raising aspirations; we need to be angry and we need to be hopeful, move away from class and gender inequality, act and speak together, to create an equal platform regardless of gender. As an example, Mandy cited the TED talk ‘Teach girls bravery not perfection’ by Reshma Saujani to further emphasise her perspectives.

Rebalancing the Bias – Is the Future Female? Panel. Day 3 of the National Photography Symposium 2018, 3 November 2018. Photography by Drew Forsyth.

As chair for the panel, Tracy Marshall stated the three strong women presented three sets of very different approaches. She questioned the speakers – how have you been touched by the sense of bias that is in photography at the moment? Hilary Wood stated it is often the case, women are in employment and more secure work environments (for security with matters such as childcare) and men are in freelance roles – this is not something that can easily change for photographers and needs to be addressed across all sectors. If we look to certain other countries, such as Sweden where there is a more gender-equal approach to maternity/paternity, this reflects a more equal gender balance in the workplace. By addressing gender parity across all industries – citing the 50:50 campaign to get more women elected in Parliament. It is also important to think of different ways to consider peer support, mentorship, and to research and explore women photographers – where they are and what they are doing. She again, returned to the key role of education; practically Further Education and Higher Education courses can be clearer on career paths for women going into photography. When we talk about representation, people think about politics, but what we need to discuss are the barriers for women in the industry – women are often seen as facilitators and background artists; we people need to think twice about who galleries and museums are going to display. It is positive that these discussions are becoming more common – let’s find constructive ways to tackle challenges. Can research be a way ahead of rebalancing gender balance?

‘Why are women not choosing women in this field?’

Responding to the Higher Education context, Maryam Wahid continued by saying she is not seeing such equality in education. Furthermore, when studying, she realised there are not many women doing work like her. She expressed concerns over the lack of women lecturers on her degree programme and during her education, not addressed until 3rd year of study. Mandy Barker emphasised, again, the need to take ownership of your career, where it is about taking responsibility for making yourself visible – it is about getting out there and creating your own opportunities, creating that platform for yourself, but where is that support to be visible? She sees a solution to this in creative roles as the idea of “flexible working”. A very powerful conversation on which to the bring to a close NPS2018.

After the close of the Symposium, an additional discussion session led by Paul Herrmann looked into where and how the National Photography Symposium and Redeye Network can develop over the next few years to service the community and sector. Presenting the idea and potential of “campaigns for the future” – what micro-actions can we make towards change in the photography sector? Four key areas were highlighted (in no particular order), including:

- Metadata – How do we gather research, identify targets and use a slogan to gain visibility of the need?

- Copyright – Specific to creative content, how do we inform photographers and work with the education sector to emphasis responsibility?

- Education – What courses and career paths are available, not limited to further and higher education?

- Gender bias – As a broader movement, what are the perceptions of this in/of photography and cultural leadership?

We would be interested in hearing your thoughts on the above – what are your key interests, issues and incentives that drive your photography and photographic practice? What do you think are key areas of change for the whole industry and can you think of issues in photography where you would like to see campaigns developed? What would you like to see the National Photography Symposium and Redeye Network develop and offer? Why not email us?

– Dr. Rachel Marsden

(Guest writer for Redeye Network)